Tuesday, 26 May 2009

Anatomy of the Google book deal

Thursday, 21 May 2009

Google proposes giving librarians a say in fees for accessing orphan works

SAN FRANCISCO — In a move that could blunt some of the criticism of Google for its settlement of a lawsuit over its book-scanning project, the company signed an agreement with the University of Michigan that would give some libraries a degree of oversight over the prices Google could charge for its vast digital library.

Google has faced an onslaught of opposition over the far-reaching settlement with authors and publishers. Complaints include the exclusive rights the agreement gives Google to publish online and to profit from millions of so-called orphan books, out-of-print books that are protected by copyright but whose rights holders cannot be found.

The Justice Department has also begun an inquiry into whether the settlement, which is subject to approval by a court, would violate antitrust laws.

Google used the opportunity of the University of Michigan agreement to rebut some criticism.

“I think that it’s pretty short- sighted and contradictory,” said Sergey Brin, a Google co-founder and its president of technology. Mr. Brin said the settlement would allow Google to offer widespread access to millions of books that are largely hidden in the stacks of university libraries.

“We are increasing choices,” Mr. Brin said. “There was no option prior to this to get these sorts of books online.”

Under Google’s plan for the collection, public libraries will get free access to the full texts for their patrons at one computer, and universities will be able to buy subscriptions to make the service generally available, with rates based on their student enrollment.

The new agreement, which Google hopes other libraries will endorse, lets the University of Michigan object if it thinks the prices Google charges libraries for access to its digital collection are too high, a major concern of some librarians. Any pricing dispute would be resolved through arbitration.

Tuesday, 19 May 2009

Fake scientific journals?

Scientific publishing giant Elsevier put out a total of six publications between 2000 and 2005 that were sponsored by unnamed pharmaceutical companies and looked like peer reviewed medical journals but did not disclose sponsorship the company has admitted. Elsevier is conducting an 'internal review' of its publishing practices after allegations came to light that the company produced a pharmaceutical company-funded publication in the early 2000s without disclosing that the 'journal' was corporate sponsored.

The allegations involve the Australasian Journal of Bone and Joint Medicine a publication paid for by pharmaceutical company Merck that amounted to a compendium of reprinted scientific articles and one-source reviews -- most of which presented data favorable to Merck's products. The Scientist obtained two 2003 issues of the journal -- which bore the imprint of Elsevier's Excerpta Medica -- neither of which carried a statement obviating [sic] Merck's sponsorship of the publication. An Elsevier spokesperson told The Scientist in an email that a total of six titles in a "series of sponsored article publications" were put out by their Australia office and bore the Excerpta Medica imprint from 2000 to 2005. These titles were: the Australasian Journal of General Practice, the Australasian Journal of Neurology, the Australasian Journal of Cardiology, the Australasian Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, the Australasian Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Australasian Journal of Bone & Joint Medicine. Elsevier declined to provide the names of the sponsors of these titles according to the company spokesperson.

Monday, 11 May 2009

Kindle's real effect on publishing ...

The piece goes into some detail regarding Kindles business model, and its unsuitability as a replacement for newspaper distribution.You know newspapers are in trouble when they tout Amazon's Kindle reader as a potential saviour for the business. Many did just that last week, and while they concluded the answer was "No", what were they thinking when they asked the question?

Today's e-readers like the Kindle bring all the expense of a computer, and all the inconvenience that comes from having to lug a computer around with you, to a medium that's cheap, portable and disposable. The Kindle's dull monochrome screen drains all the life and texture from the news - and all the branding and differentiation[*] a newspaper has built up over the decades. Put a newspaper onto a Kindle and you bury it alive in a grey digital coffin.

I'm writing as someone who has spent the last decade reading newspapers on mobile gadgets - from offline readers to the iPhone. Believe it or not, the Kindle is as nice as it gets. It's just that paper - where you can still get it - is a superior technology for browsing and reading to anything digital.

Newspapers are nervous, though, and can't think clearly. They pay enormous sums to digital shroud-wavers like Jeff Jarvis, to hear that they must commit suicide for the greater good of Web 2.0. Because Kindle makes subscribing easy - and subscriptions are a newspaper's Holy Grail - it's got the publishers twitching with excitement. Thanks to the Senate hearings last week, we now all know a little more about what Amazon is asking newspapers to do to

killsave them.

Sunday, 3 May 2009

How Google does it (book scanning, I mean)

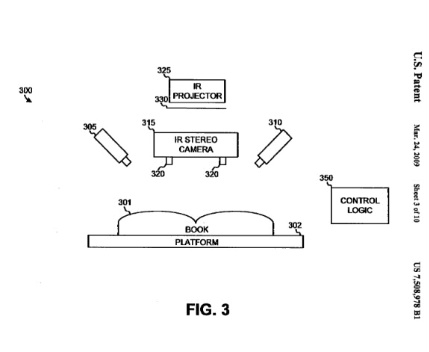

Detection of grooves in scanned images

A system and method locate a central groove in a document such as a book, magazine, or catalog. In one implementation, scores are generated for points in a three-dimensional image that defines a surface of the document. The scores quantify a likelihood that a particular point is in the groove. The groove is then detected based on the scores. For example, lines may be fitted through the points and a value calculated for the lines based on the scores. The line corresponding to the highest calculated value may be selected as the line that defines the groove.

Eh? And yet it turns out that this is the basis for Google's amazingly efficient book-scanning technology.

In a lovely blog post, Maureen Clements explains how:

Turns out, Google created some seriously nifty infrared camera technology that detects the three-dimensional shape and angle of book pages when the book is placed in the scanner. This information is transmitted to the OCR software, which adjusts for the distortions and allows the OCR software to read text more accurately. No more broken bindings, no more inefficient glass plates. Google has finally figured out a way to digitize books en masse. For all those who've pondered "How'd They Do That?" you finally have an answer.